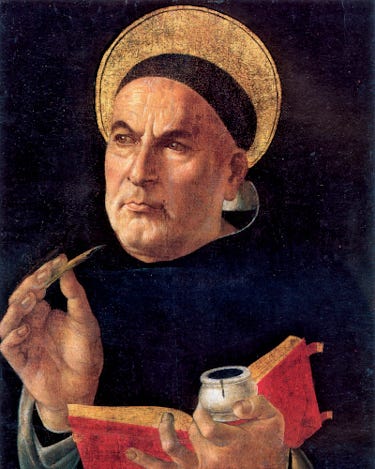

St. Thomas and Justice

Part I: The Dominicans, My Big Italian Kidnapping, and the Pope(s)

Welcome back for this first-next addition of The Pursuit of Justice, where we detail Thomas Aquinas. I felt that this would be more helpful for both of us reader2writer as we dig into modern justice and what defines it. I am trying to be entirely objective about this while understanding also that this character is a product of his environment. I cannot stress enough: this is about the pursuit of justice, elusive as it is, and I am not derogating or affirming my beliefs by discussing these figures in depth. For the most part, you can come to your own conclusions in regard to how you feel about each person we cover. I am more tooled and toiled towards the ultimate prize: justice.

This will be all free and open to discussion too. If you are in to that kind of thing anyway. By the end of this all, we want an answer to our questions in the beginning about justice, and they need to be satisfactory answers. Not saying they necessarily need to make us feel warm and fuzzy inside, but an actual answer needs to be had. This pseudo diagrammed sentence is where we are, which will be updated as we go through our pursuit of justice:

Justice/is/

Obviously this is nascent but it will continue to grow and expand until we have a good idea of what the hell justice actually is in modern thought. Let’s get started!

Aquinas’ Season

Thomas Aquinas lived in a time marked by constant warfare, intrigue in the classics, and expansion of power by the church. When we discuss Aquinas’s teachings and theory, it will be hard to escape the theological with the philosophical and vice versa.1 Aquinas, however, is a product of his environment and tried to explain the relationship between the natural, human and divine rather the work in a complete theory in how it all was supposed to work.

To set the stage a bit, we are in the “High” Middle Ages about to cross over into the ‘Late’ Middle Ages in Western Europe. In particular Italy was a concentration of wealthy and exuberant city states by the 13th century. Venice, Genoa, Milan, Ragusa, Ravenna, and Florence2 had become wealthy for trade and mercantile, while much of northern Europe was still stuck in its own feudalistic ways. The Concordat of Worms had been signed in 1122 which resolved the Investiture Controversy between the church and state.3 Pope Innocent III4 had just finished his reign in 1216, which was marked with an outreach of the Vatican’s dominion over not just Italy, but all of Europe.

Thomas Aquinas was born in Aquino, Italy around 1225 A.D. Aquinas grew up in a well-to-do Italian family in their own castle in Roccasecca, controlled by the Kingdom of Sicily.5 As his other eight siblings had military ambitions, young Thomas would be sent to the Abbey of Monte Cassino at the age of five for a more ecclesiastical pursuit with the Benedictine order. He did not remain a Benedictine, as he was convinced otherwise by John of St. Julian and sought to join the newly minted Dominican order.6

Aquinas’s family, and in particular his mother, desired Thomas to become an Benedictine Abbot at the local Monte Cassino. Feeling betrayed when he chose a different order in secret and in a last ditch effort, the family intercepted Aquinas as he tried to escape for Rome. They confined him for one year at the fortress of San Giovanni in Rocca Secca.

Family members became desperate to dissuade Thomas, who remained determined to join the Dominicans. At one point, two of his brothers resorted to the measure of hiring a prostitute to seduce him, presumably because sexual temptation might dissuade him from a life of celibacy. According to the official records for his canonization, Thomas drove her away wielding a burning log—with which he inscribed a cross onto the wall—and fell into a mystical ecstasy; two angels appeared to him as he slept and said, "Behold, we gird thee by the command of God with the girdle of chastity, which henceforth will never be imperilled. What human strength can not obtain, is now bestowed upon thee as a celestial gift." From then onwards, Thomas was given the grace of perfect chastity by Christ, a girdle he wore till the end of his life.

Hampden, Renn Dickson (1848). The Life of Thomas Aquinas: A Dissertation of the Scholastic Philosophy of the Middle Ages

I’m not sure that would be my choice via a gift from Christ, but hey times were different. All the holiness and chastity belt aside, the guy was constantly embroiled in conflict even within his own Italian family.7 Aquinas had not a duty to his family insofar as god was concerned, which seemed to inform his lectures, sermons and writings in the future. Aquinas’s primary goal was to observe and find God’s truth.

After this sidequest, Aquinas was flitted off to Paris to study philosophy for the next three years, and after that, to Cologne where he studied under Albert the Great, who would be a cornucopia of knowledge for Aquinas and would shape Aquinas’s own philosophy of sorts. This philosophy accepted Greek and Arabic works inasmuch as they could be used in conjunction with Christian teachings, which is a precursor to the Italian Renaissance. Albert represented someone who was very intrigued in Aristotle and was a leading historian and commentator in 13th Century European theology and philosophy. One of the two legacies left by Albert was his introduction of the Christian west to Aristotle and the other, his considerable influence on Aquinas.8

Thomas was nominated by Albert for the prestigious advanced theology degree in Paris in 1252, even though Aquinas was but a mere two years shy of the required age. Aquinas became the Dominican chair for theology, and earned his doctorate in Paris. He was immediately then named master in theology9 but eventually rotated out, as was Dominican custom, back to Italy in 1259.

Summa-whosa-whatsa

Aquinas is informed by his upbringing, faith, and scholar.10 In a time of strife and change nearly everywhere in his life, Aquinas went forth to explore the relation between man, church, community, and god. But that is enthusiastically when he falls short: he presupposes there is a god, which acts more as an answer than an inquiry for philosophical purposes. So when critiquing Aquinas we have to take him for what he was at the time - a Dominican Scholar who would later be blasphemed for his own manifestation of resurfaced ideas from antiquity.11

After Aquinas went back to Italy, he bounced around Naples, then Rome as papal theologian and part of Pope Clement ‘s (IV) entourage in 1265. In the same year, he was assigned to teach at the studium conventuale at the Roman convent of Santa Sabina. While at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale, Thomas began his most famous work, the Summa Theologiae, which he conceived specifically suited to beginner students:

Because a doctor of Catholic truth ought not only to teach the proficient, but to him pertains also to instruct beginners.

As the Apostle says in 1 Corinthians 3:1–2, as to infants in Christ, I gave you milk to drink, not meat, our proposed intention in this work is to convey those things that pertain to the Christian religion in a way that is fitting to the instruction of beginners.

So, the Summa Theologiae is actually supposed to be a slight trickle to a newcomer of Christianity, which informs how it is to be defined. Thomas wrote and lectured much in Italy, even with the rise of other of schools of thought in the medieval world. In response to these emerging schools of thought, in 1268 he was hurriedly summoned back by Bishop Etienne Tempier to Paris to combat Arrevvoism, termed for the famous Andalusian philosopher Averroes12, which was deemed radical at the time. Thomas went hard into Averroism, which he coined, with more works written against the concept championed by Averroes: “the unity of intellect.” We will discuss this more in length within that piece itself, but the important thing to know is that this idea is that intellect is a natural quality, rather than being something supernatural or “more than” humankind. This is an important distinction because Aquinas and his contemporaries believed in the latter rather than all human beings possessing the same amount of intellect.13

The rest of Thomas’s life teetered between academic and mystical. He was given whatever studium generale14 he liked to build with whomever he wanted working there. He set this up back in Naples and continued to preach, lead sermons and work on his Summa Theologiae. in 1273, on the feast of St. Nicholas (Dec 6th), after the celebration of mass, Thomas beheld a vision. In that mystical encounter, he saw something — saw someone. In the weeks that followed, he found himself somehow less on earth. He ceased to dictate the Summa Theologiae, though he was only midway through the section on the sacraments. He famously stated:

“I can do no more,” he said

“Everything I have written seems to me as straw in comparison with what I have seen.”

Whatever happened, Thomas never finished his works. However, the good thing is all of his other works have survived and are in such good shape even after later condemnation.

Next time, Part II and an in-depth look at Aquinas’s death, post-death reactions (omg so real) and the actual text with iterations of justice.

Thanks for reading!

- HJRC

This is intentional, since the Western tradition uses the divine to create order. Inexplicably, because justice is a value made up of morally right, the philosophy of justice will be tied up with the theological as well.

Via Matilda of Tuscany.

Prior to this event bishops, abbots, and even some popes were appointed via investiture by the Holy Roman Emperor and rubber stamped by the clergy; after, they became an exclusive papal appointee albeit with some sort of state influence through divine right. Most early medieval bishops in the church held a quasi-secular administrative function to a disintegrated Western Roman Empire and later to their successors. Holding these positions was pretty important for both nobles and those in power, considering the amount of lavish lifestyles, power and land they held.

Fucking fun fact: Innocent III annulled the Magna Carta, which in turn caused English rebellions afterward, leading to actual reform.

Normans from the Holy Roman Empire.

Honorius III (Innocent’s predecessor) officially recognized the Dominican order only in 1216, so it was safe to say that this was a new and untested pedigree for ecclesiastical studies at that time.

I lived in Italy for a year and traveled through it again a few years later; there are some things I love and some things I do not love about the Boot. I was also on my own in a foreign country, and maybe that was more of what I was feeling. I had a friend (Oklahoma Beauty Queen actually) who watched an old guy “pleasure himself” in her general direction while she was walking to the train station early in the morning. She contacted the police who really just shrugged, which was sort of amusing given her adamacy something be done. C’e Italia.

For Albert, free-will was informed by the choice between intellect and the person’s own desires. Aquinas also follows directly in this line of thinking, which is interestingly expanded upon with Aquinas actually saying someone needs to act “virtuous” to be so.

He was also too young for this position, but no one really cared.

Aquinas was, bizarrely, the first person I thought of when I wanted to research this.

The topics he discussed were: (a) not new; (b) dominated by his faith; and (c) not even that radical for the time. The intolerance of the time was such a severe impediment that most critiques now either fall in one of two lines of thinking: too god conscious or too secular. Good grief.

Not the last time we will see this guy.

This is just saying that intellect is something all people have, that can be cultivated. It is not saying that everyone is the same level of intellect or is as smart as another.

A colloquial term for medieval university.