Donnie Gaddis picked the wrong county to sell 15 oxycodone pills to an undercover officer.

If Mr. Gaddis had been caught 20 miles to the east, in Cincinnati, he would have received a maximum of six months in prison, court records show. In San Francisco or Brooklyn, he would probably have received drug treatment or probation, lawyers say.

But Mr. Gaddis lived in Dearborn County, Ind., which sends more people to prison per capita than nearly any other county in the United States. After agreeing to a plea deal, he was sentenced to serve 12 years in prison.

The above excerpt is from this New York Times Article in 2016 looking into the unequal sentencing in rural vs urban communities. The trend used to be more people ended up in jail in more urban centers because, duh, there is a more sizeable population (and higher levels of poverty). Recently, however, that trend has changed. If you live in rural areas now, you are twice more likely to end up in jail.

In 2020, the homicide rate grew 30% in urban areas and 25% in rural areas according also to the NY Times. You are far more likely to die in a homicide or car crash in rural america than urban america. Rural america is a vibrant and peaceful alternative to city life, and I think growing up where I did (Blue Mountain AR - Pop 132) gave me a unique perspective on this. But there are problems with small time America. The urbanization trend has left rural areas such as Blue Mountain with the lack of resources, population, and access to justice comparable to its urban counterparts.

Hold on, isn’t putting people in jail a good thing? It protects our communities from those pending trial for a violent offense, and then keeps them there post-conviction. Restricting and taking away someone’s freedom for community safety is the point of jail, if not the definition. Arguably even putting someone on probation is an restraint on their freedom, and there is always the fear you could get sent to jail. But jail is the ultimate penalty from a constitutional, moral, and sociological view (I don’t count the Death Penalty, more on that another time). You’re commanding someone to spend time in a place other than their home and to be treated to sometimes very substandard living arrangements. There’s a reason we have a very fancy and complicated way of adjudging guilt in the U.S. : We want it to mean something.

But what has been driving this trend of pro-incarceration in rural communities? Some pin it on the loss of jobs and prevalence of the opioid crisis. For them, the landscape of crime has changed. Those are factors, to be sure, but there has to be someone who suggests jail instead of treatment or non-jail alternatives. Drug overdose deaths in rural counties have reversed themselves in recent years, and reportedly more people want to move out to the rural country for more space. So that explanation isn’t based in recent reality. That’s where decision making and D.A. Office’s policies come into play.

“In the big city, you get a ticket and a trip to the clinic. But in a smaller area, you might get three months in jail.”

Jacob Kang-Brown, senior research associate at the Vera Institute of Justice.

Balance

More people incarcerated leads to generally negative sociological and demographic outcomes. I think if you’re reading this you likely agree with me, but we will take it back a walk. It’s about balance. We need to balance the outcomes of more community safety vs more incarceration. What does that look like?

“Community Safety” is a fickle term. Let’s think about Ted Bundy who represents the most extreme threat to community safety there is as one person (let me know in the comments if you disagree). I’m not counting number of deaths here, just sheer malice. I mean the dude escaped twice in Colorado, went to a completely different state to then just pop up in Tallahassee and kill two FSU Sorority sisters. I regard Bundy as the most violent and malicious “criminal law textbook” killer you could have. His crimes read like my Criminal Procedure II final exam (HE’S LIKE FOUR MPC1 CRIMES AT ONCE).

Anyway, Mr. “Heartless Evil” himself killed more than 25 people, mostly young girls and women between 1974-1978. The U.S. Population was about 200 million, and increased about 8 million between those dates. Tallahassee had about 72,624 people in 1970 and grew about 10k in the next ten years. So Bundy killed 0.003% of the population and got the electric chair. He was an efficient killer; from a number’s standpoint he was close to the most confirmed kills (34, Samuel Little) out of individuals considered “serial killers.” That has to count for something right?

But community safety isn’t just a measure of kills to total population - it’s about fear and to do something normal like send your kids to school without that fear without wondering if you will be next. It’s about perception of danger rather than actual societal danger.

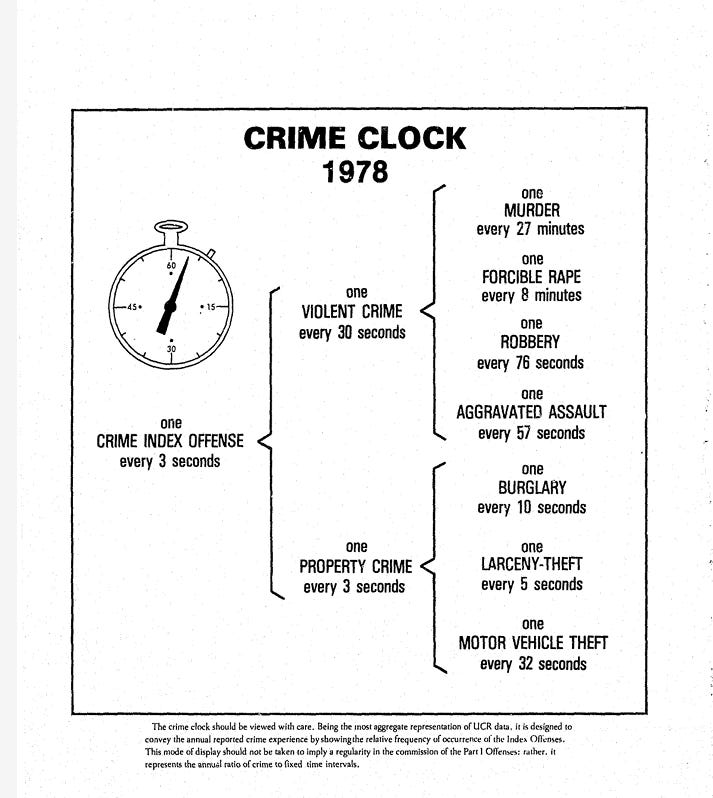

Ted Bundy is also just one man. Violent crime in the U.S. was pretty high in 1978, with this scary infographic from the baby FBI UCR:

The U.S. crime index total was 5,109.3 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1978 (FBI-UCR 1978). Tallahassee (where FSU is) itself was 7,755.5 per 100,000 inhabitants. Needless to say, the higher crime rate in Tallahassee contributed to the overall atmosphere of fear in 1978 when Bundy attacked four women and killed two within fifteen minutes. If anything, the Ted bundy serial killer angle only amplified the fear in that community that already existed.

Similar results were reported by the Harris poll of 1975, which found that 55 percent of all adults said they felt "uneasy" walking their own streets. The Gallup poll of 1977 found that about 45 percent of the population (61 percent of the women and 28 percent of the men) were afraid to walk alone at night. An eight-city victimization survey published in 1977 found that 45 percent of all respondents limited their activities because of fear of crime: A statewide study in Michigan reported that 66 percent of respondents avoided certain places because of fear of crime. Interviews with a random sample of Texans in 1978 found that more than half said that they feared becoming a serious crime victim within a year.

U.S. Dept of Justice, 1988 “Perspectives on Policing”

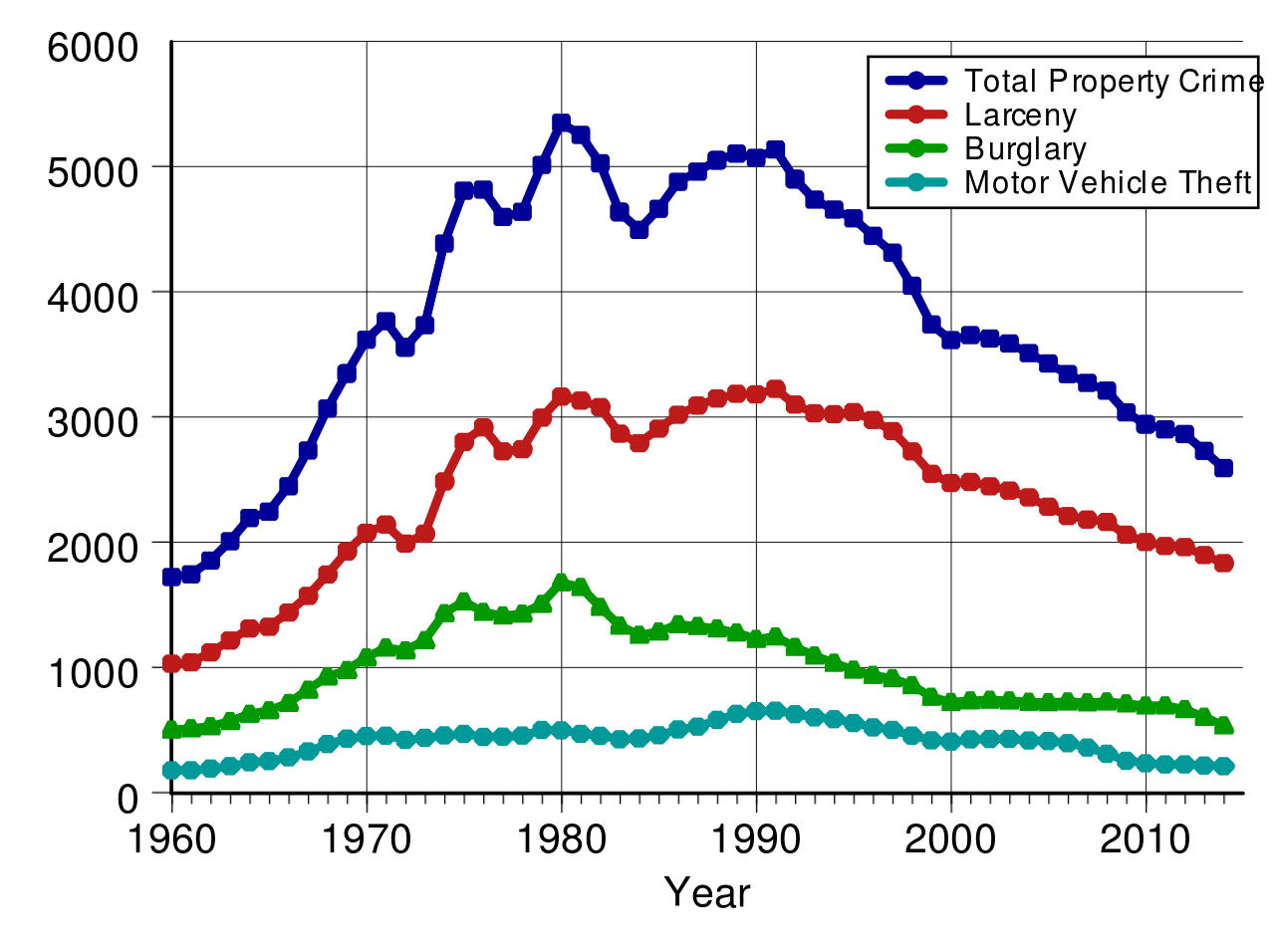

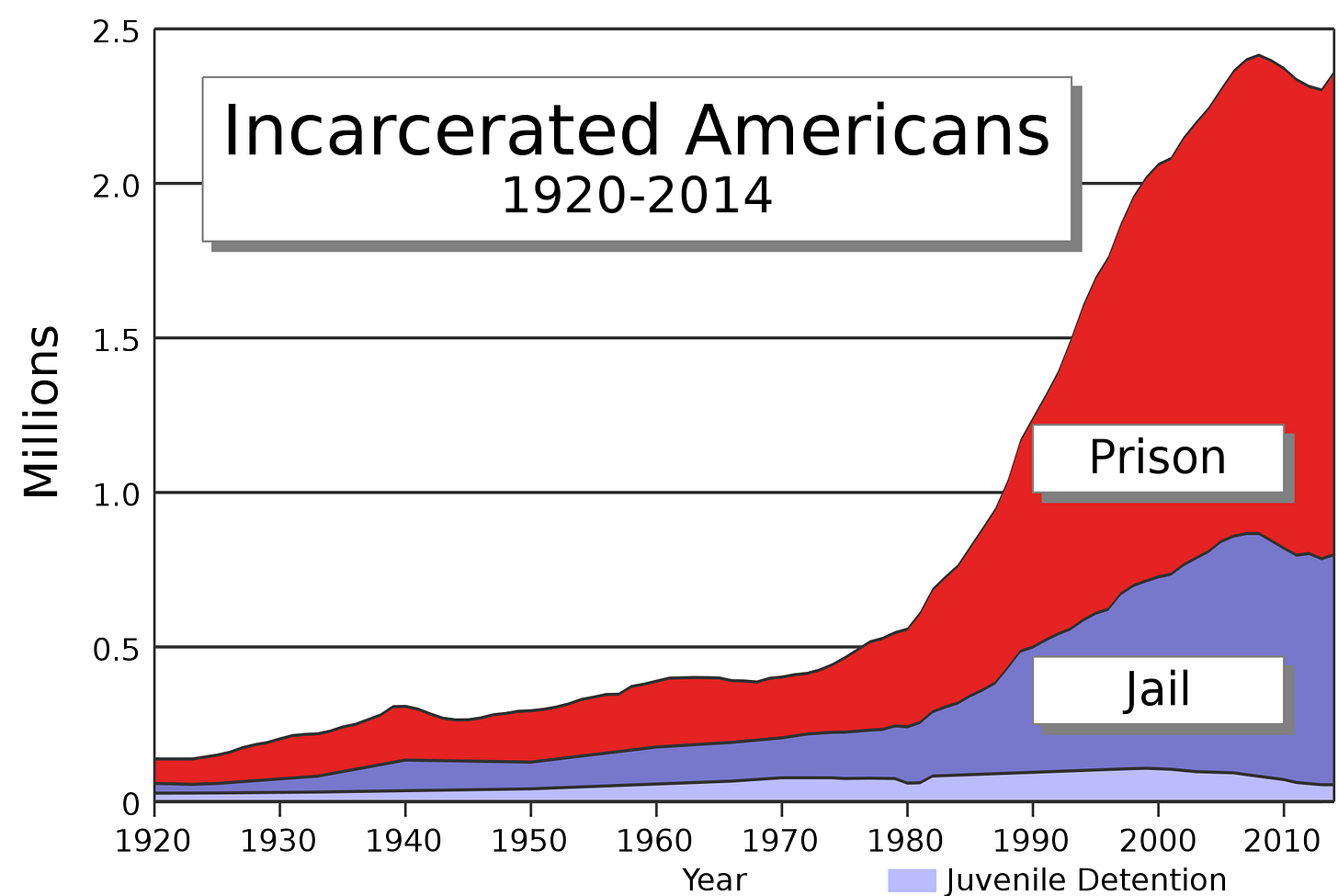

But does jail remedy that? Take a look at these two graphs.

It appears there is a spike in jail populations in the 1980s when crime was high in the U.S. but after the 90s, the prison and jail population keep…booming. Somewhere along the line, it seems like the U.S. decided it would eradicate crime by jail, and it worked for a bit. I already cover this here. However, it seems like the U.S. decided to not change its policies. Starting with Clinton in the early 90s with the largest crime bill ever in 1994 (Billy!) and continuing with G.W.Bush’s “Texas Solution” and Patriot Act Passage in the 2000s (his 1994 gubernatorial campaign slogan was “Incarceration is Rehabilitation”). The proportions are off too, because if the U.S. kept imprisoning people at that kind of a clip, shouldn’t crime be eradicated?

But we forgot about people in jail/prison because of probation and parole holds (violations of parole/probation).

The most recent data show that nationally, almost 1 in 5 (19%) people in jail are there for a violation of probation or parole, though in some places these violations or detainers account for over one-third of the jail population. This problem is not limited to local jails, either; in 2019, the Council of State Governments found that nearly 1 in 4 people in state prisons are incarcerated as a result of supervision violations. During the first year of the pandemic, that number dropped only slightly, to 1 in 5 people in state prisons.What’s on the other side of the scale? Well, mass incarceration means more poverty (food insecurity, housing instability, reliance on public assistance) and whole a lot of unintended side effects on the kids who are growing up now or have already grown up and dedicate their life to domestic terrorism. Or are one of the 10 million who commit domestic violence every year. Or shoot up a school of children (more than once), a theater of people, a crowd in Las Vegas, or simply steal to survive. It seems as if the solution to crime with jail only begets more crime.

Prison Policy.org, The Whole Pie 2023

If I may, the easier way to characterize “Community Safety” and “Mass Incarceration” is short term vs long term effects, is it not? I’m not saying there’s a better one or the other here. What I am saying is, like everything, there’s gotta be a balance. Are there people like Ted Bundy that need to be put in jail? Absolutely. Do drug users? Absolutely not. Drug traffickers? Maybe. It depends. It depends on adequate resources to prosecute the drug traffickers effectively but at the same time defend people like Ted Bundy competently. Where are places with adequate resources and a budget to do so? Not rural America.

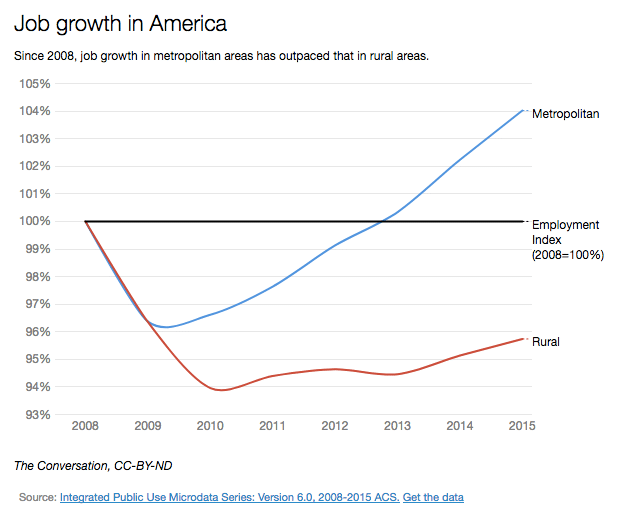

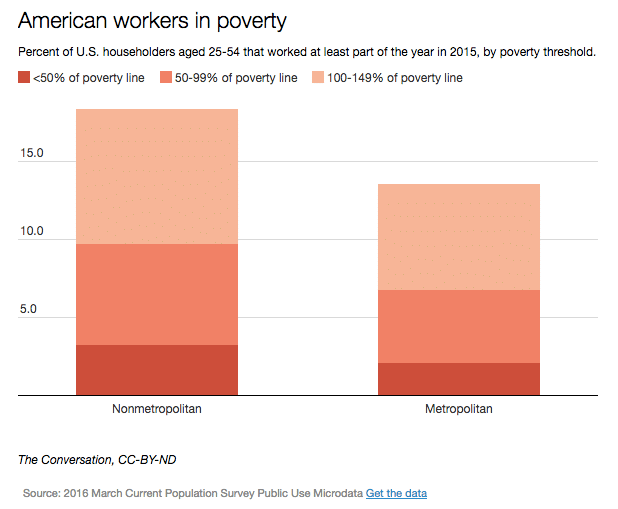

And since 2015/17 it has only widened with Covid-19 and economic instability. From 2010-2020 rural America’s population change was a -0.6% and urban America grew +8.8% (2020 U.S. Census). Country towns and Rural America have taken a hit, and the lack of funding, jobs and competent justice systems has exacerbated it.

So let’s summarize. Jail is the ultimate penalty. It is a balancing act between community safety (short term effect) and societal implications from sending more people to jail (long term effects). Rural jurisdictions have seen bigger increases in crime than before, with violent crime in particular increasing. People in rural parts of the U.S. go to jail at twice the rate urban people do. This is because of a combination of factors, including lack of resources and the pro-jail policies in rural DA Offices, which may be dependent upon each other.

Because this is a quasi-legal/statistical type writing, I’m going to start with a null hypothesis and question presented type format. I’ll work from there.

Null hypothesis: If policies are pro-jail and the number of people going to jail in rural areas is higher than urban areas, then there is no correlation between policies for political capital by elected DAs (and it only has to do with scarcity of resources).

Question Presented: Does scarcity of resources, such as adequate funding for alternative programs, cause more rural jurisdictions to be more pro-jail, or is it impacted by “tough on crime” policies for political gain?

Foundational Data

Lack of Resources

There are a lot of articles out there that talk about the lack of rural lawyers. Supply and demand comes into play, but attorneys that are straight out of law school want to be paid. Why do they want to be paid? Debt. For example, I went to an affordable law school and still have nearly 100 grand in debt. Some people go to Ivy Leagues, or massive state schools to get their J.D. without in-state tuition. If you are doing that by yourself, you have even more debt. Or not, and you can afford to go wherever your heart desires rather than something that will make you money. I’m looking at you intergenerational wealth 1%er’s. You need to pay back the money you loaned, so you need to be paid an adequate enough salary. The money is typically in urban areas (shocker). Most law school grads are going straight through from undergrad, so it would be fair to say they average between 25-30 years old when receiving their J.D.

At my time at the University of Arkansas, many local lawyers and professors implored us to think about rural lawyering because there will be jobs and you have a real chance to give back to the community. I came from rural Arkansas, see above. Closest food was 15 miles away, usually closed after 7pm. I couldn't think of something that would be more of an antithesis to what I wanted to do, so I moved to rural Colorado to be a Deputy DA. All jokes aside, my first intuition was not to go to rural places, which has to be most late 20 to early 30-somethings idea. Cities are vibrant with things to do and people to see

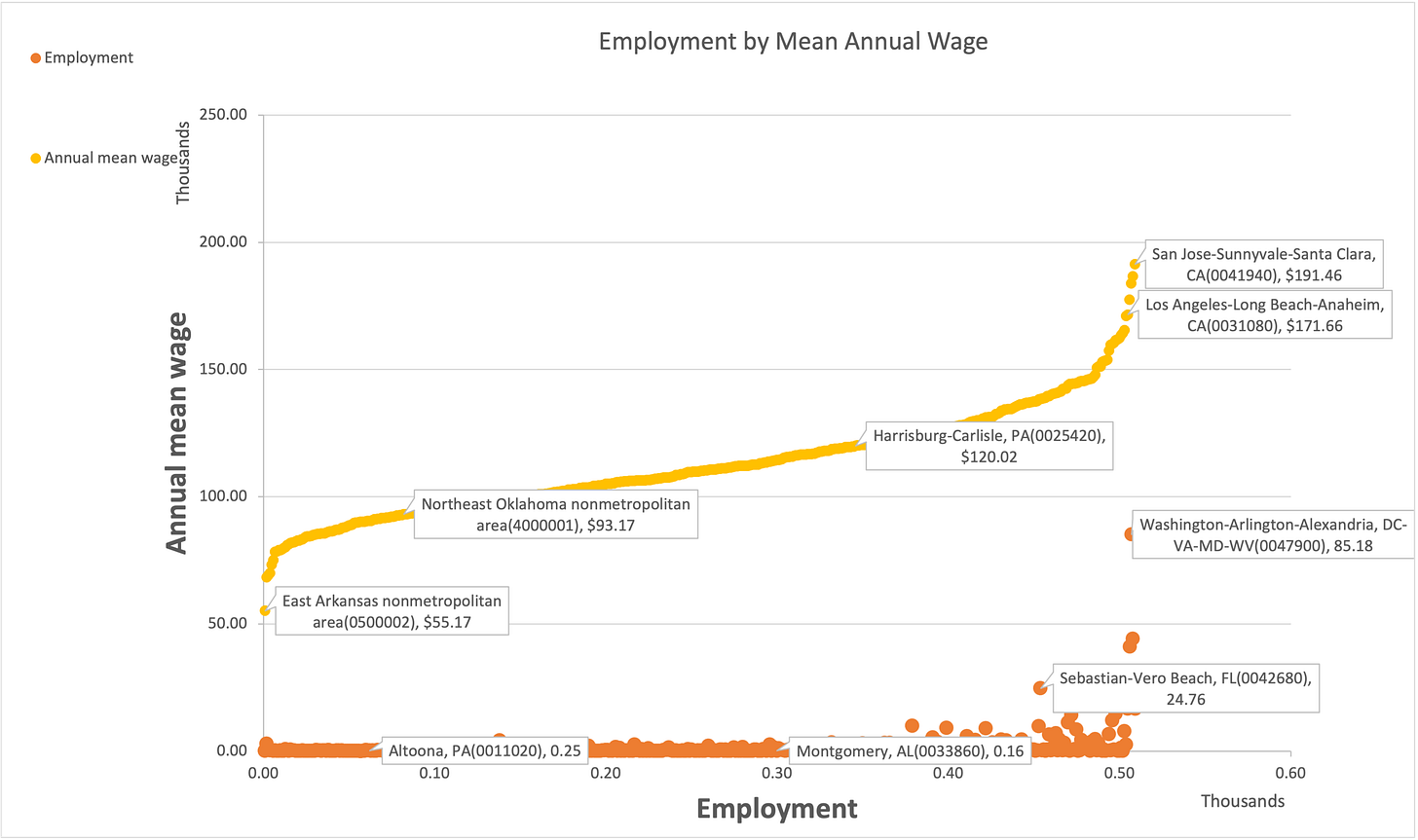

I want to get to the heart of the question, does bigger and more resources always mean better? Or is there something else? So, I collected some data from the U.S. Labor Statistics for May 2021.

I took all the regions and split them by metro and non-metro areas. Then I looked at the average mean of wages from May 2021 (the latest) and employment in those offices, using a scatterplot to see where they landed and to see if there was a relationship. It looks like bigger urban areas have higher pay and more employees, which is expected. But there are still pretty staggering numbers to consider.

In the top 25 out of all 510 regions, there are 12 California regions. California lawyers makes a whopping $3,657,950.00 in total annual salaries for their 150,960 lawyers both in Metro and Non-Metro areas. To put that in perspective, there were 665,200 total lawyers in May 2021 and California had 22% of all lawyers in America. California's total lawyer pay was about 6% of what the national total was. Texas had a little higher of a number, which probably indicates the similar population levels more than anything. But there is an important distinction between these two states: California has their own bar exam and doesn't follow the Universal Bar Exam (UBE) like Texas now does. This is typically a barrier to lateral hire lawyers moving to California and keeps lawyers there for a longer time period.

Now that's just lawyers. Which can exaggerate the type of income spreads here. But you have to think that government prosecutors are being paid at the low end of the barrell. Example? The San Francisco average for a DA is about $98,00-$113,000 but compared to the average attorney salary at $202,777 it seems like small potatoes. An assistant DA in New York makes on average $70,000 a year but compared to a general New York Attorney? Say Michael Cohen?

I'm kidding. But it's between $180k and $300k (even without the hush money). So it is safe to say that comparatively, low level DAs make about a third of the salary their other lawyer counterparts do. Why is this? Typically, counties manage and set the budget for DA offices, and those counties aren't necessarily the most flush with cash in rural jurisdictions or even in urban ones. The government likes to be efficient with its money, which usually means budget cuts and cumbersome red tape.

At the end of the day, if you want to recruit new talent from law schools or otherwise lateral hires, you have to:

Political

When asked, the Dearborn County elected District Attorney said:

"I am proud of the fact that we send more people to jail than other counties... that's how we keep it safe here."

He added in an interview: “My constituents are the people who decide whether I keep doing my job. The governor can’t make me. The legislature can’t make me.”

Aaron Negangard, 2015-2016 NY Times

In 2014, Mr. Negangard ran unopposed as the incumbent in Dearborn County Indiana (Pop about 50,000). Something key here is his reference to "my constituents.” But when you’re the only DA in the county running, isn’t it disingenuous to say that the constituents will hold you accountable? Going down the rabbit hole, Mr. Negangard endorsed Curtis Hill for AG in 2016 (who won), whose law license was then suspended by the Indiana Supreme Court in 2020 for inappropriately touching four women, one a state legislature rep, in 2018. Guess who got the interim post when Hill stepped down? Aaron Negangard, a member of his staff as Chief Deputy AG.

So what is this former elected Dearborn County DA doing now? Well, he ran for judge of the Ohio Seventh Circuit Court....unopposed. Um....I would think that it is likely hard to capture the actual feeling for the whole of your population without there being another candidate to give the constituent’s options. So on its face, it looks like democratic process. But in reality, and with shifting economic and crime landscapes, this looks more like there is sham electioneering as the only horse and pony show in town. So the policy for jail rather than alternative programs is something a county is pretty much stuck with, sometimes for multiple terms.

If this web of political chaos is confusing, it should be. But that’s exactly what this is: political. In a pretty neat article on Filter Mag, (and this interesting author pic) they interpret the findings from a National Study on elected prosecutor retention statistics. They found that the majority of these elections for counties with a population of less than one million have a single, unopposed candidate—while counties with over one million people generally see a contested election. 74% of DAs in districts with fewer than 100,000 residents run unopposed, but that number diminishes to 63% for counties with between 100,000 and 250,000 residents.

It also details some pretty crazy acts on behalf of DAs in their elected counties. One interim DA that was beat by a more progressive and Democratic candidate in 2018 in Massachusetts mounted a write in campaign to undermine the result, but still ended up losing. Another in 2012 in New York actually sued the county because of the term limits law implemented. He ended up winning, but then it caught up with him...with a Federal conviction to four counts of corruption. He still refused to resign initially when he was indicted.

Public Servants

District Attorneys and their prosecutor staff are public servants. The CDAC (Colorado DA Council) defines it like this:

District attorneys (DAs) are dedicated public servants who are charged with seeking the truth and pursuing justice under the law on criminal matters that occur in their jurisdiction.

The term public servant comes from the establishment of civil service which has its roots in Imperial China, under the Imperial Examination process in the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE). This continued, until it was more formalized later on by the Song Dynasty and then taken back to Europe by the British in the 18th century. The first modern rendition of civil service was British East India Company (yes, those guys) in 1806. It’s important to note that these exams or posts were held by merit, not birth, which was different than the way most of Europe did things in those days.

The Northcote–Trevelyan Report of 1854 made four principal recommendations in regard to how to organize the British Civil Service: that recruitment should be on the basis of merit determined through competitive examination; that candidates should have a solid general education to enable inter-departmental transfers; that recruits should be graded into a hierarchy and that promotion should be through achievement, rather than "preferment, patronage or purchase" (Kazin, Edwards, and Rothman (2010), 142.)

America, a Commonwealth Nation, followed suit and reformed it in 1883 with the Pendleton Act following the assassination of President James Garfield. It specifically says this:

Fifth, that no person in the public service is for that reason under any obligations to contribute to any political fund, or to render any political service, and that he will not be removed or otherwise prejudiced for refusing to do so.

Sixth, that no person in said service has any right to use his official authority or influence to coerce the political action of any person or body.

and it goes on…

SEC. 12. That no person shall, in any room or building occupied in the discharge of official duties by any officer or employee of the United States mentioned in this act, or in any navy-yard, fort, or arsenal, solicit in any manner whatever, or receive any contribution of money or any other thing of value for any political purpose whatever.

If you are a fan of constitutional originalism and civil service, this would be your Act. Zachary Karabell, a pretty important contemporary writer by his own marks, says that the Pendleton Act was instrumental in the creation of a professional civil service and the rise of the modern bureaucratic state (Chester Allen Arthur, pg 108-111, 2004). The modern civil service (PACE) exam has still been criticized for racial quotas and have "raised serious questions about the ability of the government to recruit a quality workforce while reducing adverse impact", according to Professor Carolyn Ban.

Isn’t this at odds with how “public servant” is interpreted with elected District Attorneys? Sure, you could make the same argument with Presidents and Congresspeople, but that defeats the purpose of “for the people by the people.” U.S. Attorneys aren’t elected, they are appointed by the President. Judges typically aren’t elected either, and they are appointed by the President or executive of a certain state (depending on the level of judge) in order to preserve that political independence the Pendleton Act sets out. The U.S. AG is a cabinet member, not elected. So why aren’t District Attorneys in states appointed?

Some are. In three states, DAs are appointed by a high officer in some manner: Alaska, Connecticut, and New Jersey. D.C. doesn’t count because its not technically a state, and the DA is the U.S. Attorney who has jurisdiction over that district. Alaska is rural, whereas the other two have dense populations. I wonder if things are different there than say other states where they elect their District Attorneys. Stay tuned for Part II.

Outro

Throughout the proceeding Parts (II and III) here, we are going to look at the actual data between rural and urban DAs in reference of resources, the lack of that data and transparency, whether we can better quantify prosecutor efficiency and justice, and finally, if it makes more sense to appoint rather than elect your DA. Remember, the Null hypothesis is what I need to disprove, not the Alt hypothesis I must prove. Here is where we are:

Alternative Hypothesis: If there are more people going to jail in rural areas, then it is because of the political agenda and policies by elected District Attorneys to send more people to jail as an appeal to community safety.

Null Hypothesis: If there are more people being put in jail in rural areas compared to urban, then it has nothing to do with elected DAs and their policies to appeal to public safety as a political mechanism.

Thanks for reading, see you soon.

-HJRC

Model Penal Code