YEAAAAAAHHHHH BOIIIIII. Welcome to the new format; new year, new me, new you, new fire in LA, new (old) president, new tomfoolery from the Feds and criminals alike. Let’s get sort of settled in here:

It is hard to know what is real and what is not out there, and being enlightened to Artificial Intelligence is something I only use in my day job, not in publication of this nor ever will I.

This is the promise I make to you.

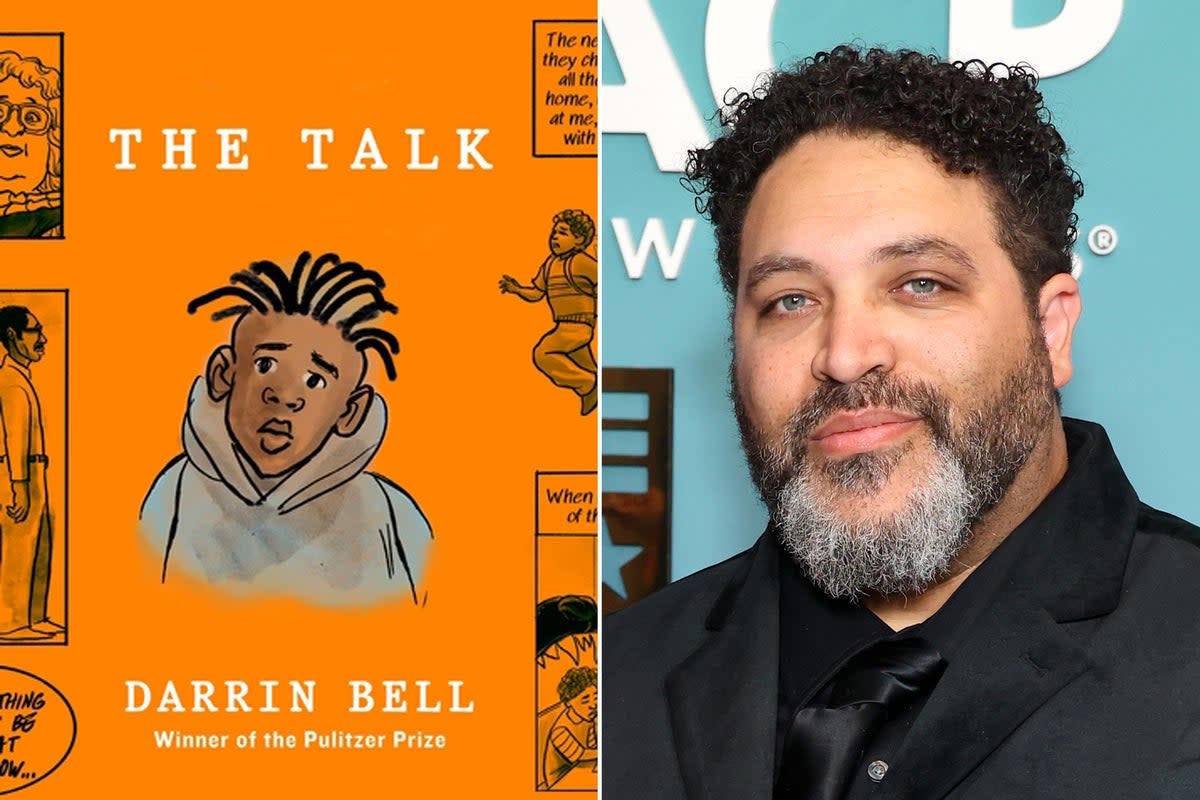

Example: Darrin Bell who was arrested yesterday for charges of child pornography. The kicker? The child porn was AI generated. California (where he resided) passed a law that came into effect in the new year to take out the loophole that child pornographers had found with AI generated child pornography.1

Bottom line: Some Substack writers sell their publications by writing with AI.

Well I don’t, so fuck them and fuck you too.2

Now that we have that out of the way, who in the name of OJ Simpson knows how justice works? I have an idea of what it is only informed by a political science and law degree, which means I can gesture wildly with my hands, say a multitude of things and nothing at the same time. As my wife and colleagues will attest, I am proficient at this. I can’t think of a better host or emcee than myself for the next adventure into this cornucopia of justice.

Justice is synonymous with the American Criminal Justice System (ACJS) because justice is what a prosecutor seeks for the crime victim that has no other recourse. Justice is also what a defense attorney gives their client via an acquittal, who was wrongly accused. The essence of justice has to be this quest for the ‘right’ outcome. What is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ is somewhat debatable depending on your persuasion. But justice as a concept is amorphous and extremely fluid, depending on which side of the ACJS you are on. One person’s justice is another’s oppression and persecution.

The format of this will be somewhat historical and something biographical of sorts. In talking about the different manifestations of justice, there’s a bit of groundwork. Justice, the concept, is something that is a literal and pretty expansive. Justice is tied closely to morality, virtue and struggle, and so these will be other veins in which we look at the just. The most pressing questions on justice we will focus on here are:

Does justice as a general concept, contemplate the ‘making whole’ of everyone in society, or of only those wronged?

Does justice serve only those who are pure or does justice apply to those who are on the fringe of society and have wronged others?

Does the criminal justice process itself seem fair when looking objectively at it?3

Does the addition of amatuer juries de-legitimize the otherwise fair criminal justice process?4

Is justice, in any sense, accomplished by killing the perpetrator of the harmful act?5 To what degree does that person need to have harmed another or society in order to exact enough punishment for a just outcome?6

Is it justice if someone gets a just result through unjust means? To what degree?

Life of the Just and Famous

A Short History of Lady Justice in the West up to the Protestant Reformation

Justice, as a concept, first reared its head in antiquity. Lady Themis7 was the goddess and personification of justice, divine order, law, and custom. She is one of the twelve Titan children of Gaia and Uranus, and the second wife of Zeus. She is associated with oracles and prophecies, including the Oracle of Delphi. Notably her symbol are the Scales of Justice. Themis means "divine law" rather than human ordinance, literally "that which is put in place", from the Greek verb títhēmi (τίθημι), meaning "to put."

“Themis is untranslatable. A gift of the gods and a mark of civilized existence, sometimes it means right custom, proper procedure, social order, and sometimes merely the will of the gods with little of the idea of right.”

Moses Finley

The World of Odysseus, rev. ed. (New York: Viking Press), 1978: 78, note.

Themis was the goddess of divine law - the primal, unwritten laws governing human conduct which were first established by the gods. Notably, her children represented both the good (The Horai) and the bad (The Morai) of human life.

"Truly upon mortals cometh swift of foot their evil and his offence upon him that trespasseth against Right (themis)."

Aeschylus, Fragment 9 Bacchae (from Stobaeus, Anthology 1. 3. 26) (trans. Smyth) (Greek tragedy circa 5th C B.C.)

In dissecting lady justice i.e., Themis, we see that the law was a structure not defined by our own and natural ideas of “right and wrong” but rather, a divine authority that told ancient peoples what to do and what not to do. But this could have just been a way to self-preserve the group rather than divine inspiration. At the very basic level, killing another human being is bad because you are getting rid of other members of the group for mankind (as the race) to survive. From an early antiquity level, the human population not very high so naturally, you’d like to preserve the group for the survival of the race. Things were more than a little at those times, and so you can’t have your own citizens killing each other when they could be killed by any number of things otherwise. You need to protect the herd.8

In antiquity, we also had the first introduction of codified law from Ur-Nammu, King of Mesopotamia 4000 years ago. This is before the Code of Hammurabi.

Here’s an excerpt from the prologue:

“Then did Ur-Nammu…establish equity in the land; he banished malediction, violence and strife … The orphan was not delivered up to the rich man; the widow was not delivered up to the powerful man; the man of one shekel was not delivered up to the man of one mina.”

The code was presented as a list of “if, then” scenarios, with crimes and punishments spelled out in striking detail. For example:

“If a man, in the course of a scuffle, smashed the limb of another man with a club, he shall pay one mina of silver.”

Note that the Code of Hammurabi was much more harsh (eye for an eye) which could represent a one of the first responses to an increase in violent crime trend in the ancient world. Babylonian scholars state that this code was actually more of a recording of past judgements, like precedent in case law, rather than a creation of law. Importantly, both of these codes allegedly emanated from divine powers.

It was also a lot easier to justify these things through the divine rather than the material. In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was a god, and thus all power flowed through him. This justified their luxury in life and in death. Rome marked a different jumping off point in the shift in power but their laws were still informed by the divine and auspicious. After Julius Caesar, the emperor assumes the role of god in human form again, and then Octavian (Augustus) slid in with his reforms that feigned the return of republican institutions before 0 A.D. In the Levant, Judaism had found purchase and stipulated to a code of laws, the Ten Commandments. There were also other jewish customs that adhered specifically to morals i.e., the designation of “kosher” foods which premised that certain animals were clean to eat and others were not.

After 0 A.D. Christianity continued to inform morals for individuals via the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. For the next 1200 years, this idea of the “god- king” in which all laws emanate becomes the standard in Europe and Western civilization. This is a continuing theme we see in the history of the law until the Magna Carta is signed in 1215 in England. The “divine right” theory gives the king the exclusive dominion over the law, because the divine made him king.9 Even after 1215, it still took many wars and a few reformations before universal suffrage came onto the scene. The transformation into this legal independence is a long story of paternalism and patriarchy. We can end this part with the beginning of the 1400s with the birth of Martin Luther, because after that, the idea of individual liberty becomes synonymous with justice. The next few centuries of the Protestant Reformation, English Civil Wars, Enlightenment, and the explosion of colonialism, and consequently revolutions, throughout the Western World will shift to emphasize individuals over the collective.

If we can summarize justice before 1200 A.D., it would look more like worship rather than adherence to principles. Someone considered just here is simply obedient to God. However, this justified anything the god-king could do to you as well, meaning that there was not justice you could obtain against the government. If you opposed, you were unjust and could be jailed or killed. This push and pull between corrective9 and distributive justice10 is something that continues on to present day and continues to stymie our crime and punishment system.

Ancient Justice in the East

You thought I would just dip out after giving you a summary of Western political thought. Surprise! With over 5,000 years of culture and innovation, Ancient Eastern Civilizations11 and China boast that they were arguably doin’ it first while the West was pogrom happy and stuck in it’s own ass for centuries. For China and the Far East, justice was represented as more of a moral flavor rather than the divine. This is through the idea of virtue, which is mirrored in writings and teachings from Aristotle and Socrates. It is important to note that this idea of virtue was at the heart of Confucianism, Mohism and Taoism which were similar philosophical schools of thought adopted to a degree like religion in China12 and spanned not only China but also most of the Far East.13 These schools of thought focused on virtue through morality, which differed from the Western philosophy of virtue through religion.

“Moral integrity constitutes the foundation of ruling while criminal punishment serves as a tool.”

Shen Deyong quoting: The Code of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.), Authoritative Annotations

This virtue was represented by tolerance, discipline and prudence, core teachings of Confucius. Allegedly this represented Chinese judicial culture through its history. I’m not entirely sure how much I necessarily believe that with human sacrifice as the only direct evidence of the Shang Dynasty. The Zhou Dynasty introduced The Mandate of Heaven as a political tool to replace the Shang. Part of this was premised on the Shang rulers own morality in justifying the Mandate. The Mandate could also be explicitly lost if the Zhou rulers acted with malice and improper practices like the Shang.14 This offers a different way in which to think about the rulers, which are at the leisure of the gods compared to where the ruler and the god or gods are the same being.

But the Zhou also developed a feudal system during their reign (1046 – 256 BC) which necessarily depended upon individual discipline of each fiefdom in order for the entire Zhou dynasty to work. As long as society was kept in order, the individual only matter as the cog of self-preservation for the entire machine of China. So the Zhou were maintaining order, but another manifestation, at least in rhetoric, was impunity.

Whenever there is any reasonable doubt with a case, we’d rather wrong the younger brother than the elder one; rather the nephews and nieces than the uncles; rather the rich than the poor; rather the unruly than the obedient. If the case involves properties, we’d rather wrong the officials and gentries than the average people so as to save ills from happening. If the case is about quarrels and dignity, we’d rather wrong the humble than the noble in order to preserve social normality.

Hai Rui, Chinese Judge (January 23, 1514 – November 13, 1587 A.D.)

This comparison is important for our talk about justice, because in understanding how people interpret it, we can make our own judgement calls about what is just and not. Western culture used religion to control the masses and inform morality whereas the Eastern approach varied only in form really. Both used religious ideology to justify their rule, but the West imbued it with the god-king whereas the East used morality based on the individual.

Next time, justice in the Western world of reformation and Eastern isolationism.

Thanks for reading!

-HJRC

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Much Ado About Something to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.